Quick Facts

Name

Robson Square

Type of Landscape

Vancouver urban core

Public Greenspace

Location

Robson Street, Vancouver

GPS 490 17’4.578” N and 1230 7’29.3664 W

Designation

Launched with Robson Square Project, 1973-1980

Owner

Province of British Columbia / City of Vancouver

Legacy

Master Planning + Urban Design

On-structure Landscapes

Introduction

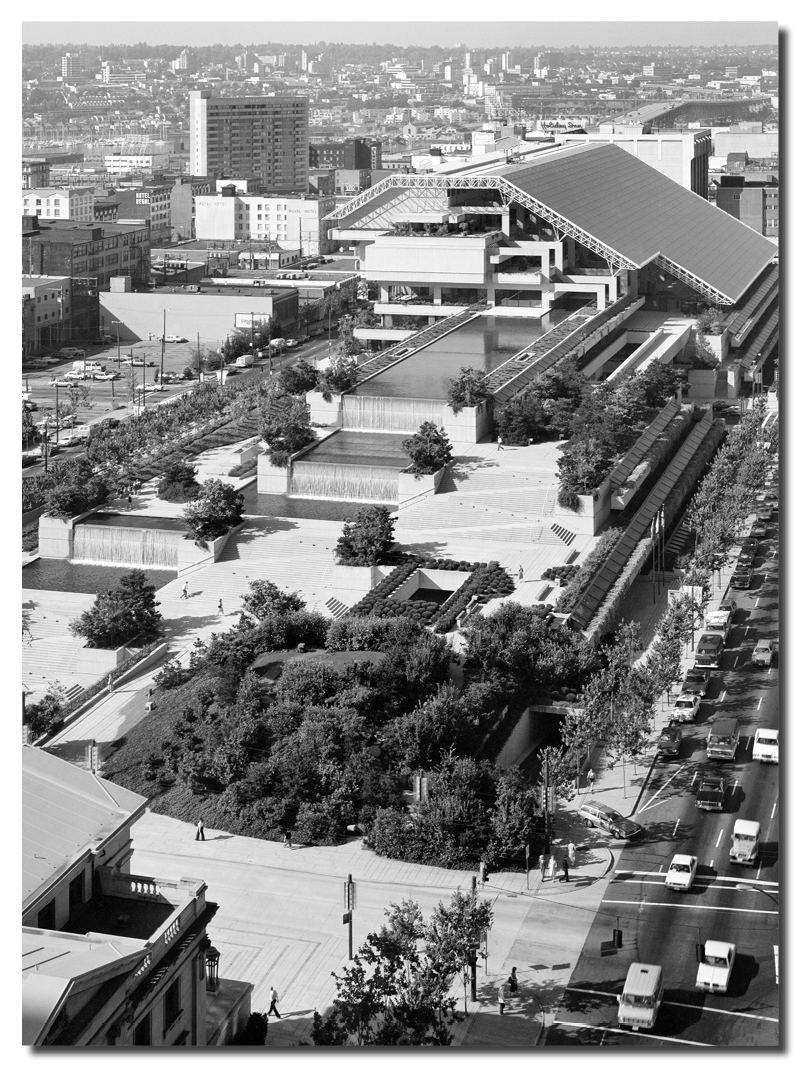

In the early 1970s, architect Arthur Erickson proposed a radical design for Robson Square that signaled the transformation of downtown Vancouver - a skyscraper “lying on its side” with green public open spaces. Working with Erickson and his team, landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander was instrumental in realizing these green spaces, and reclaiming the city’s downtown for the people of Vancouver.

The plans were, at the time, audacious. When Robson Square was first conceived, Vancouver’s downtown was not the dense, vibrant enclave that it is today. Green spaces were almost non-existent; surface parking lots furnished the chief open areas. Yet Robson Square was to become a three-block long, park-like oasis of gardens, plazas and buildings, a place for gathering by day and by night.

The design intention was distinctly modern, the technical challenges numerous. To design an airy, multi level, topographically interesting landscape on grey city blocks, Oberlander successfully situated almost all natural elements – plants, soil, water, and 50,000 trees and shrubs – on the central block. The feat attracted wide-spread attention. By pioneering several emerging technologies, Robson Square had expanded the boundaries of the landscape architecture profession.

Importantly, the designers carefully integrated the landscape with existing buildings and Erickson’s architecture, including government, judicial and commercial spaces that offered entertainment. In the centre block, waterfalls and sculpted terrain were so seamlessly worked into the landscape that the topography appears to be carved from the depths of the ground.

In less than a decade, it had become a highly-valued, urban gathering place for Vancouverites, a site for social and cultural exchange, and a catalyst for urban revival. In 2008, Vancouver architectural critic Trevor Boddy labeled Robson Square, “Vancouver’s largest and best-loved living room.”

Robson Square illustrated that landscape architecture was integral to the urban aspirations of Vancouver, and an inspiration for cities across the country.

Planting on Buildings: Vertical Relationships

When Cornelia Hahn Oberlander joined the Robson Square design team as its chief landscape architect, she immediately recognized that Arthur Erickson’s conceptual design was built upon complex relationships between interior building elevations and exterior landscape levels.

To understand the vertical changes within the three-block site, Oberlander developed a matrix for all outdoor spaces. How might landscape design features at each level be modified to evoke new sensations, stimulate new activities?

For recurring landscape features like water basins, for example, a change of elevation triggers a change in size. As water moves down across the south and centre blocks of Robson Square to approach street level, the basins become successively smaller. The sound of falling water increases, helping mute traffic noise at the street.

The inventive variety of Oberlander’s multi-level landscapes also unified the diverse architecture, which ranged from a 1911 neoclassical Provincial Courthouse (now the Vancouver Art Gallery) to the north, and a new Law Courts to the south.

Exterior and interior spaces were inventively combined on the Law Courts block and centre block, with roofs supporting extensive planting areas; an interior glass ceiling providing a water basin on the plaza level; and structural walls serving as exterior waterfalls. At the central block, a low-profile structure was largely camouflaged by the water and vegetation that Oberlander conceived in three typologies: walkway plantings, box planters, and “flying planters” cantilevered from the building facades.

It was the 50,000 shrubs and trees, primarily on structures, that commanded the greatest attention. Oberlander was the Canadian pioneer of emerging green roof technologies, including computerized irrigation and fertilization techniques, new waterproofing membranes, and light-weight growing mediums. In 2009, when the original waterproofing systems needed an overhaul, many of her original plantings were saved and maintained.

A High Point: The Mound

The spot which most poignantly embraces the project’s goals to reclaim the city for the people was Oberlander’s mound at the corner of Robson and Hornby streets. Perched almost eight metres above the plaza level and crowned with extensive planting, this spot was a place where people, according to Oberlander, “feel like they are not in the midst of a city.”

The Legacy: Urban Aspirations

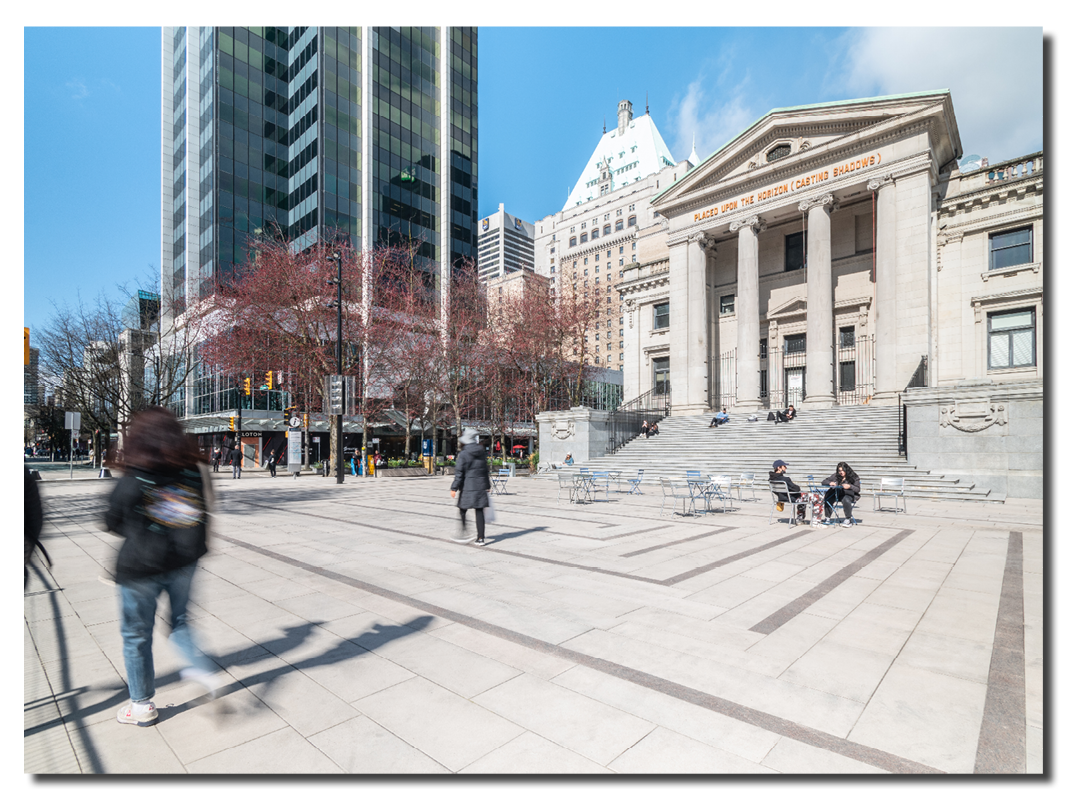

A half century after its inception, Robson Square’s cherished “living room” remains a central gathering space, a green respite in what is now a very different urban core. The project has been a catalyst for development, attracting the dense urban housing that now characterizes downtown Vancouver.

Like Vancouverites, international crowds are drawn to Robson Square for its central city location and its programs. When Vancouver hosted the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, over 1.5 million people came for the free ice-skating in the sunken plaza, the performances, and the zip-line.

It is also a place for activism. The stairs of the Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG), in particular, serve as a podium for political demonstrations, HIV and AIDS activism, rallies against war and economic oppression, and calls for climate change action. In 2019, Greta Thurnberg spoke here during the Climate Strike March. In 2021, Haida artist Tamara Bell placed 215 pairs of children’s shoes on the steps, creating an impromptu memorial and collective place for Indigenous healing.

Robson Square continues to build on its strengths. Most recently, lead landscape architect Joseph Fry (Hapa founder) led the transformation of the North Plaza of VAG, and then turned the 800 block of Robson Street into a pedestrian plaza. Both sites reinstate pink and grey pavers reminiscent of Robson Square’s original design.

The architectural historian, Kenneth Frampton, equates Robson Square at its inception with Rockefeller Center in the 1930s, which spurred the growth of Manhattan. Today, Robson Square continues to provoke change within the city and beyond. It defined an emerging area of expertise in green roof design, spurring on an entire industry – a giant step forward toward more ecological, more human, places.

Loving the Stramps

Robson Square’s elegant and often replicated “stramps” quickly became iconic.

The hybrid stair/ramps, which first offered places to sit and reflect, have been adopted in many other urban landscapes. One of the most prominent stramps was created in 2012 at Clock Tower Beach along the Quai de l'Horloge in Old Montréal. Claude Cormier et Associés (now CCxA) designed these stramps as an homage to Cornelia Hahn Oberlander from Claude Cormier.

The Cultural Landscapes Legacy Collection highlights the achievements that have made a lasting impact within the field of landscape architecture and on communities across Canada.