Quick Facts

Name

Fortress of Louisbourg

Type of Landscape

National Historic Site

Location

Louisbourg, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia

GPS: 45.89, -59.99

Timeline

French colonial fortress and town: founded 1713; destroyed 1758.

Stewards

Parks Canada

Legacy

Archaeology

Heritage Interpretation & Research

Introduction

Almost three centuries ago, in the 1740s, a remarkable fortified city of some 4000 civilians and French military personnel prospered on Cape Breton’s shores. The Fortress of Louisbourg, with its cosmopolitan city design, its elegant French colonial homes and richly planted gardens, was a booming commercial hub, welcoming trade and citizens from across the seas.

The garrisoned city, quickly constructed in only a few decades, was of profound significance as Britain and France struggled for Empire and for control of the rich cod fishery off Canada’s Grand Banks. Sadly, in 1758, British forces besieged the city for the second and final time, and its short and tumultuous history as a French hold ended. It was systematically destroyed in the years that followed.

In the aftermath of the destruction, a small community began to blossom on the outskirts of the former fortified town. The site itself was never significantly redeveloped until the 1960s. With the decline of coal mining on Cape Breton Island, the government began a partial reconstruction of the fortress site, hoping to launch a new, more sustainable industry – tourism. The two decades that followed saw what would be, and remains, the largest reconstruction of an historic site in Canadian history.

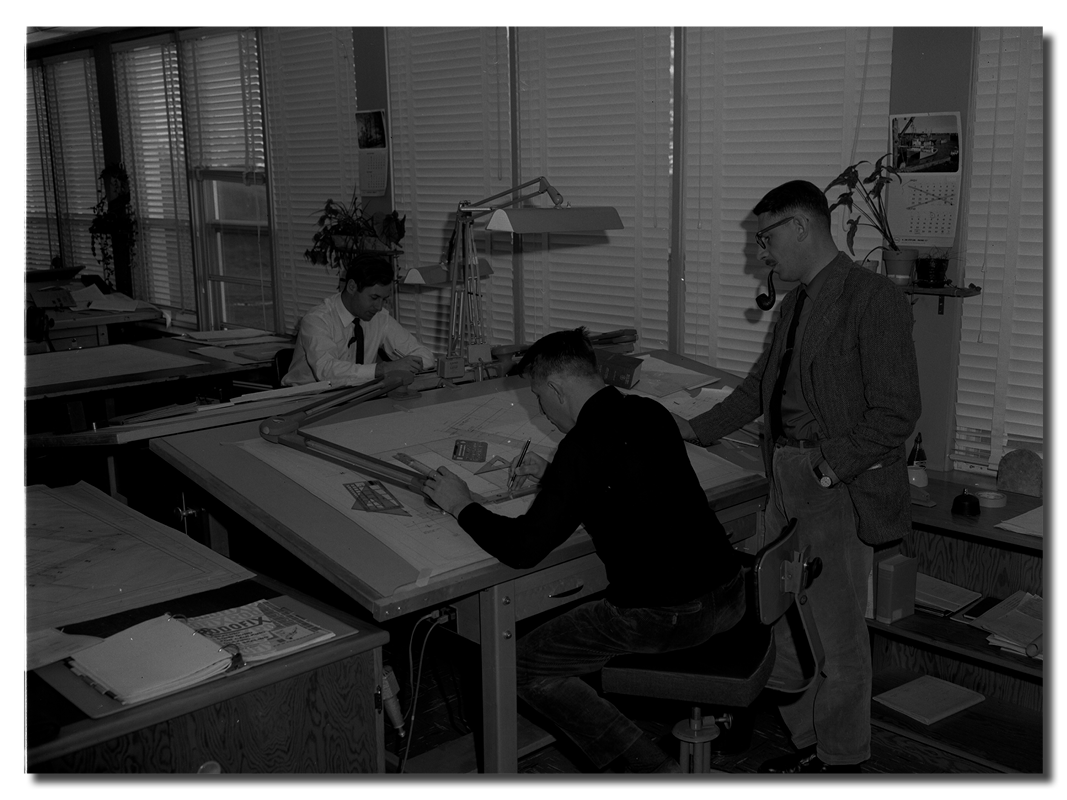

The task was formidable. Parks Canada commissioned teams of architects, historians and archaeologists to authentically recreate the 18th-century town long destroyed, using original drawings that had been preserved in France. Louisbourg became the birthplace of historical archaeology in Canada, and a massive repository of conservation knowledge.

Since the 1980s, countless tourists have been drawn to Cape Breton, to visit the French colonial town brought to life once again. The Louisbourg experience is an incredible opportunity to connect with stories of this place, exactly where its stories were lived and written.

In the Beginning… Rising from the footprints

Despite the complete lack of existing 18th-century built works remaining intact on Cape Breton’s shores, the beautiful Louisbourg fortress and townsite did indeed come to rise again.

The reconstruction was a Herculean task. The colonial town had long-since been completely destroyed; only building foundations remained. But from that barely visible beginning, the multi-disciplinary teams began their studies of the landscape, bent on recreating at least a quarter of the site.

The researchers began well, locating the original town-site plans for Louisbourg in France. The city, in 18th -century fashion, was laid-out on a perfectly rectangular grid. The Fortress, too, could be recreated with confidence, since precise drawings existed for similar works, with protective bastions and batteries. Over decades, researchers discovered more than 500 maps, thousands of photographs and hundreds of thousands of document pages. Working together, the architects, landscape architects, archaeologists, historians, and conservators assembled a massive collection of more than 5.5 million artifacts and a massive GIS database.

With evolving teams of experts from dozens of fields, they recreated the thriving Louisbourg of 1744 before the British sieges began to destroy the town. Today, Louisbourg once again boasts greenery in dozens of yards and gardens, busy streets full of carts and music, elegant homes, a King’s Bakery and scores of detailed works that bring the centuries-old, colonial capital authentically to life.

Unearthing the Stories: Hundreds of Gardens

“The city of Louisbourg was graced by a large number of gardens, formal and elegant for high officials, simple and functional for commoners,” wrote Ron Williams, in Landscape Architecture in Canada. There had been, he noted, “more than a hundred gardens within the city, most of them bounded by picket fences and laid out in square or rectangular planting beds bordered with shrubs or flowers.”

Given the constant shortage of foodstuffs, most were essentially practical (fruit gardens, kitchen gardens). But since no detailed plan has ever been found of a particular garden site, the garden reconstruction teams at Louisbourg created representative gardens, using plants and techniques harvested from a variety of sources: cookbooks, gardening books, letters, documents, seeds and pollen. The archaeological record provided clues as well.

“Included among the plants identified, from Native sources as well as the mother country, were cabbages, beans, onions, carrots, and squashes, usually placed in the middle of planting beds; anise-seed (caraway), hyssop, lavender, and spearmint at various locations; and blue iris along with carnations, bellflowers, and pansies as borders.

“Vertical planks were used to raise the level of beds, and wood was used for staking and supporting plants according to several traditional techniques.” — Excerpted from Landscape Architecture in Canada, with the kind permission of author Ronald A. Williams

The Legacy: The Epic Continues

Reclaiming the past is an ongoing job, reaching across centuries into the present. At Louisbourg, three-quarters of the site is resting still, hidden beneath turf and forest, pasture and knoll.

New discoveries proliferate as teams of specialists unravel the landscape’s history and the lived experiences of those who once occupied this town. Every year, scores of story-tellers and planners, interpreters and volunteers, blacksmiths and bakers, authentically bring the town’s stories to life.

For some 70,000 visitors a year, the fortress experience is an incredible opportunity to connect with Louisbourg’s unusual history. For the vast community of those who work on the heritage sites, Louisbourg embodies generations of learning.

Almost a half century ago, the project became a case study in exploring how and when reconstruction should be managed in places of historic significance. While many of the steps taken at the site in the 1960s would not be considered best practice today, even the missteps, carefully recorded, informed current methods of preservation and re-creation. Louisbourg’s massive knowledge base is a key resource for professionals, both inside Canada and abroad.

Still, there is work to be done. Every artifact, every landscape, needs constant care. Landscapes do not remain static. In our century, climate change is bringing sea level rise, coastal erosion and increased storm activity. Original 18th-century shore protections are no longer sufficient. Landscape architects, together with other scientists, are searching for answers. Similarly, built heritage teams are devising ways to make the site more accessible to all visitors, pioneering new designs and methods that are sympathetic to the town’s historic character.

Louisbourg is destined to remain a work in progress that is of intense interest to visitors and specialists alike.

Image: Parks Canada

The Cultural Landscapes Legacy Collection highlights the achievements that have made a lasting impact within the field of landscape architecture and on communities across Canada.