Quick Facts

Name

Canada’s Capital Landscapes

Type of Landscape

Urban Ethnographic Landscape

Natural Landscape

Location

Ottawa, ON; Gatineau, QC

GPS 45° 24' 40.21" N, -75° 41' 53.23" W

Stewards

Government of Canada : National Capital Commission

Legacy

Master Planning and Urban Design

Transportation

Recreation/Health & Well-Being

Introduction

The story of the transformation of the Ottawa region from a sub-arctic wilderness portage to an attractive modern capital city is little known, outside of the Capital itself. The site’s magnificent natural setting – waterfalls, cliffs, boiling rapids and dense forests – was well-known to Indigenous Peoples for millennia, but difficult for European settlement. By the late nineteenth century, the settlers had established lumber industries, which marred the considerable natural beauty of the site.

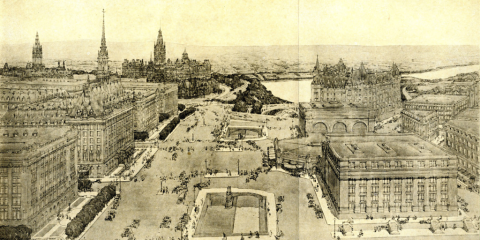

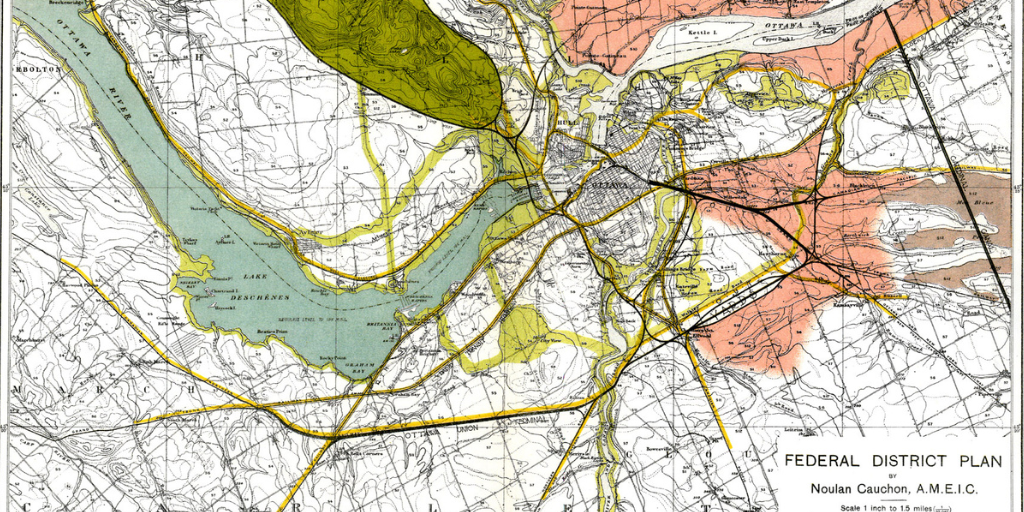

The federal government made repeated attempts to plan and develop its seat of government, starting with a 1903 parks system report by Olmsted protégé Frederick Todd and a 1915 City Beautiful plan by Beaux-Arts trained urban designer Edward Bennett. Todd prepared a preliminary parks plan for the entire Canadian capital region, including both sides of the Ottawa River. Unfortunately, the Ottawa Improvement Commission declined to retain him. Nonetheless, Bennett incorporated many of Todd’s parks and parkways, as did Jacques Gréber, the prominent French urbanist and landscape architect, whose later work would set the stage for future decades.

The Gothic Revival Parliament Buildings and their hilltop grounds were magnificent, but by the end of World War II, the collapse of the lumber industry, Depression and wartime “temporary” offices hid the natural beauty of its landscape.

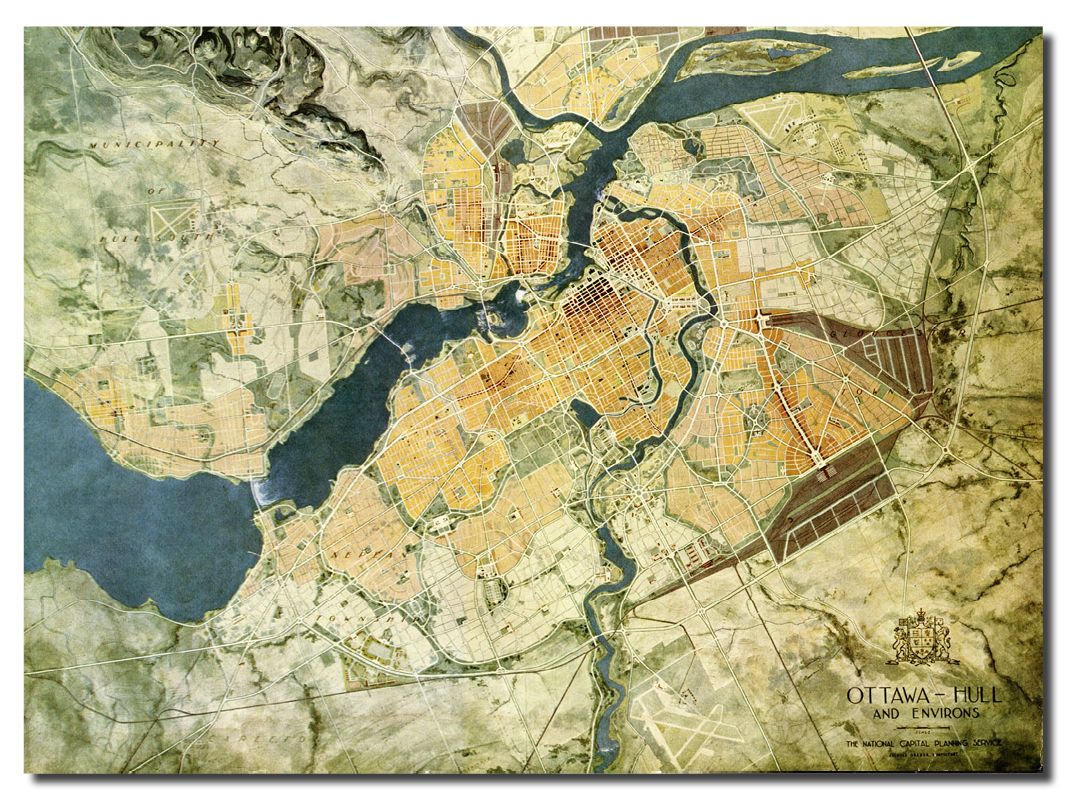

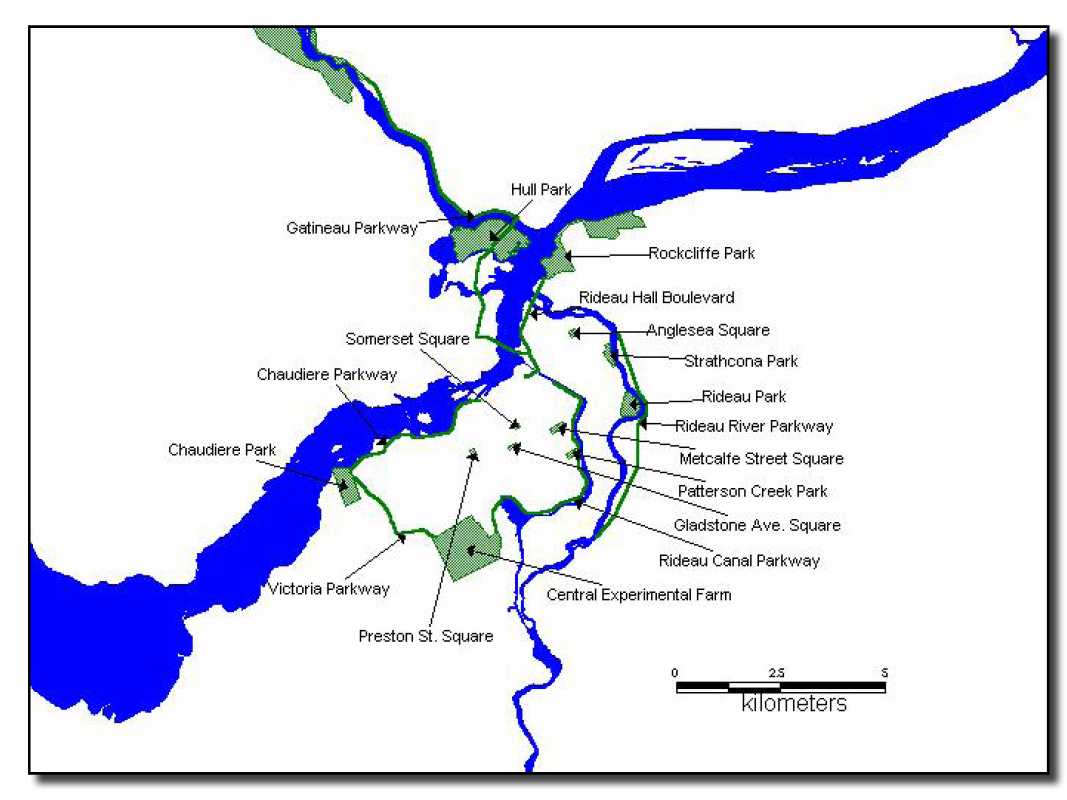

Prime Minister Mackenzie King was embarrassed to host other world leaders which made creating a beautiful national capital Canada’s principal memorial to those who served in WWII. He personally selected Gréber to design Confederation Square, the site of Canada’s War Memorial (1939), and then to lead the planning team for the 1950 Plan for the National Capital. This document would serve as the guide for the rapid transformation of Ottawa and Hull from dreary industrial towns to an attractive and functional modern capital (1950-1970). The plan led with large-scale and highly visible landscape projects: opening up Gatineau Park, expropriating a huge Greenbelt, developing large parks and knitting these open spaces together with an expanded parkway system.

The result was a pleasingly green capital city, with a high quality of life for its residents.

On the Hill

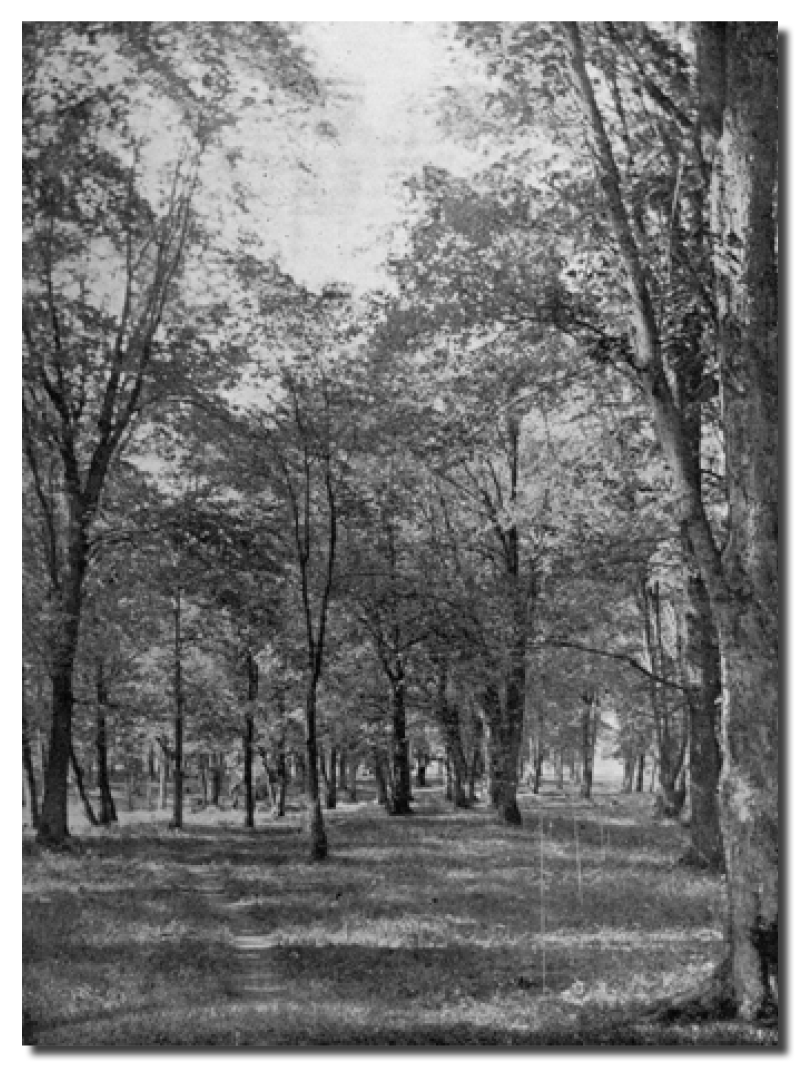

Calvert Vaux, the man who co-designed New York’s Central Park with his protégé F. L. Olmsted, was the first landscape designer to leave an indelible imprint on Canada’s capital. Vaux, who was a fan of the Gothic Revival style of Canada’s magnificent parliamentary complex, prepared an elegant landscape plan (1873) which skillfully tied together the differences of elevation on the magnificent site, with its spectacular viewscapes to the river below. Vaux took full advantage of the dramatic hill-top, adding an upper terrace with viewing bays and stairs. The pedestrian approach to the hill, the wrought-iron and stone enclosures, and indeed the overall topography still exist. All long-established character defining elements of the Hill to this day!

Calvert Vaux, the man who co-designed New York’s Central Park with his protégé F. L. Olmsted, was the first landscape designer to leave an indelible imprint on Canada’s capital. Vaux, who was a fan of the Gothic Revival style of Canada’s magnificent parliamentary complex, prepared an elegant landscape plan (1873) which skillfully tied together the differences of elevation on the magnificent site, with its spectacular viewscapes to the river below. Vaux took full advantage of the dramatic hill-top, adding an upper terrace with viewing bays and stairs. The pedestrian approach to the hill, the wrought-iron and stone enclosures, and indeed the overall topography still exist. All long-established character defining elements of the Hill to this day!

A Succession of Talent: The Ottawa Timeline

The enviable grace and greenery of Canada’s National Capital Region by the year 2000, was a composition that had demanded the dedication of a long succession of Prime Ministers, commissioners, and designers, and a century of patience.

Despite the dignified grace of Vaux’s work on Parliament Hill, it would take another generation, and the strategic leadership of the spirited Ottawa Improvement Commission (OIC), to bring another visionary Olmsted-connected planner to the city: Frederick Gage Todd. The OIC, guided in its early years by such luminaries as Lady Aberdeen, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, and Governor-General Earl Grey, inspired the government to commission Todd’s parks system plan (1903).

Unfortunately, the plan languished for another decade, until the Federal Plan Commission (1913-16) hired another remarkable talent, Edward Bennett (1914-16), who admired Todd’s ideas. But Bennett’s 1915 plan, too, all but disappeared during the tumultuous 35 years of war and depression that followed.

By the end of World War II, Ottawa and Hull still resembled factory towns, yet the time was ripe. As early as 1910, Ottawa planning commissions had a staunch ally in future Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King. King actively supported capital planning for over 40 years, until his death in 1950. His government established the Federal District Commission (1927- 1958), the forerunner of the National Capital Commission (NCC). By 1934, the Commission hired its first staff landscape architect, Edward I. (Ned) Wood, who for a remarkable 30 years, would superintend the sweeping changes to come.

A National Capital Planning Committee (1945-50), established to hire the best talent, brought Jacques Gréber back to the city after the war. From 1946-1950, Gréber focused unceasingly on the comprehensive plan to build a world capital. Working with the essential support of the NCC‘s Wood and landscape architect Douglas McDonald, plus scores of independent Canadian landscape architects, city planners and architects, Gréber led a planning team capable of a two-decade miracle: the transformation of a decaying lumber town into a modern, expansively green capital. By 1970, the work was well begun, but in the decades ahead, the NCC’s leadership was needed on larger, inter-regional issues and on capital city elements such as cultural institutions, view corridors, monuments and embassies.

From Decaying Lumber Town to Green Capital

By 1970, the National Capital Region was a destination worthy of Canada, but the work was far from complete. Almost every decade brought a new capital plan: 1974; 1988, and the plans of 1999 and 2017 which included an extensive parks system.

These sweeping improvements created a more cosmopolitan, eco-friendly city.

- Confederation Boulevard (1983+; duToit Allsopp Hillier)

- The Parliamentary Precinct plans (1986+; duToit Allsopp Hillier)

- The revised Greenbelt plan (1996), which looked beyond failed sprawl control to conserving ecological systems

- The Plan for Canada’s Capital (2017), focused on the Ottawa River landscapes

The National Capital Commission (NCC), which rapidly became a country-wide model, was one of the first commissions in Canada to form a design review committee of distinguished landscape architects, architects and planners. And in the 1970s and 1980s, when local/regional/federal infighting threatened to derail ongoing work, it was NCC Chair Jean Piggott (1985-92) who broke the gridlock.

By the early 2000s, Ottawa’s capital had become an iconic winter capital, boasting the world’s longest skating rink (Rideau Canal), and a wealth of recreational winter landscapes along city rivers and in the parklands of Gatineau Park. In summer, the capital region has become an outdoor paradise. Its varied downtown green spaces host huge summer crowds for Canada Day, festivals and splendidly varied walks, and Gatineau Park draws locals and visitors to the surrounding hills and lakes. The Capital has regularly ranked highly on global live-ability ratings.

The Cultural Landscapes Legacy Collection highlights the achievements that have made a lasting impact within the field of landscape architecture and on communities across Canada.